Non-parametric Methods

Adam J Sullivan

Assistant Professor of Biostatistics

Brown University

Non Parametric Statistics

What are they?

- Non parametrics means that you do not need to specify a specific distribution for the data.

- Many of the methods you have learned up to this point require data dealing with the normal distribution.

- This is due partially to the fact that the t-distribution, \(\chi^2\) distribution, and the \(F\) distribution can all be derived from the normal distribution.

- Traditionally you are just taught to use normallity and made to either transform the data or just go ahead knowing it is incorrect.

Normal vs Skewed Data

- Data that is normally distributed has:

- the mean and the median the same.

- The data is centered about the mean.

- Very specific probability values.

- Data that is skewed has:

- Mean less than median for left skewed data.

- Mean greater than median for right skewed data.

Why is this an issue?

- In 1998 a survey was given to Harvard students who entered in 1973:

- The mean salary was $750,000

- The median salary was $175,000

- What could be a problem with this?

- What happened here?

Why do we use Parametric Models?

- Parametric Models have more power so can more easily detect significant differences.

- Given large sample size Parametric models perform well even in non-normal data.

- Central limit theorem states that in research that can be perfromed over and over again, that the means are normally distributed.

- There are methods to deal with incorrect variances.

Why do we use Non Parametric Models?

- Your data is better represented by the median.

- You have small sample sizes.

- You cannot see the ability to replicate this work.

- You have ordinal data, ranked data, or outliers that you can’t remove.

What Non Parametric Tests will we cover?

- Sign Test

- Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test

- Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test (Mann-Whitney U Test, ...)

- Kruskal Wallis test

- Spearman Rank Correlation Coefficient

- Bootstrapping

The sign Test

The Sign Test

- The sign test can be used when comparing 2 samples of observarions when there is not independence of samples.

- It actually does compares matches together in order to accomplish its task.

- This is similar to the paired t-test

- No need for the assumption of normality.

- Uses the Binomial Distribution

Steps of the Sign Test

- We first match the data

- Then we subtract the 2nd value from the 1st value.

- You then look at the sign of each subtraction.

- If there is no difference between the two groups you shoul have roughly 50% positives and 50% negatives.

- Compare the proportion of positives you have to a binomial with p=0.5.

Example: Binomial Test Function

- Consider the scenario where you have patients with Cystic Fibrosis and health individuals.

- Each subject with CF has been matched to a healthy individual on age, sex, height and weight.

- We will compare the Resting Energy Expenditure (kcal/day)

Reading in the Data

library(readr)

ree <- read_csv("ree.csv")

ree

## # A tibble: 13 x 2

## CF Healthy

## <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 1153 996

## 2 1132 1080

## 3 1165 1182

## 4 1460 1452

## 5 1634 1162

## 6 1493 1619

## 7 1358 1140

## 8 1453 1123

## 9 1185 1113

## 10 1824 1463

## 11 1793 1632

## 12 1930 1614

## 13 2075 1836

Function in R

- Comes from the

BDSAPackage

SIGN.test(x ,y, md=0, alternative = "two.sidesd",

conf.level=0.95)

- Where

xis a vector of valuesyis an optional vector of values.mdis median and defaults to 0.alternativeis way to specific type of test.conf.levelspecifies \(1-\alpha\).

Getting Package

# install.packages("devtools")

# devtools::install_github('alanarnholt/BSDA')

Our Data

library(BSDA)

attach(ree)

SIGN.test(CF, Healthy)

detach()

Our Data

##

## Dependent-samples Sign-Test

##

## data: CF and Healthy

## S = 10, p-value = 0.02

## alternative hypothesis: true median difference is not equal to 0

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## 25.4 324.5

## sample estimates:

## median of x-y

## 161

##

## Achieved and Interpolated Confidence Intervals:

##

## Conf.Level L.E.pt U.E.pt

## Lower Achieved CI 0.908 52.0 316

## Interpolated CI 0.950 25.4 324

## Upper Achieved CI 0.978 8.0 330

By "Hand"

- Subtract Values

library(tidyverse)

ree <- ree %>%

mutate(diff = CF - Healthy)

ree

By "Hand"

- count negatives

## # A tibble: 13 x 3

## CF Healthy diff

## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 1153 996 157

## 2 1132 1080 52

## 3 1165 1182 -17

## 4 1460 1452 8

## 5 1634 1162 472

## 6 1493 1619 -126

## 7 1358 1140 218

## 8 1453 1123 330

## 9 1185 1113 72

## 10 1824 1463 361

## 11 1793 1632 161

## 12 1930 1614 316

## 13 2075 1836 239

By "Hand"

binom.test(2,13)

##

## Exact binomial test

##

## data: 2 and 13

## number of successes = 2, number of trials = 10, p-value = 0.02

## alternative hypothesis: true probability of success is not equal to 0.5

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## 0.0192 0.4545

## sample estimates:

## probability of success

## 0.154

Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test

Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test

- The sign test works well but it truly ignores the magntiude of the differences.

- Sign test often not used due to this problem.

- Wilcoxon Signed Rank takes into account both the sign and the rank

How does it work?

- Pairs the data based on study design.

- Subtracts data just like the sign test.

- Ranks the magnitude of the difference:

8

-17

52

-76

What happens with these ranks?

| Subtraction | Positive Ranks | Negative Ranks |

|---|---|---|

| 8 | 1 | |

| -17 | -2 | |

| 52 | 3 | |

| -76 | -4 | |

| Sum | 4 | -6 |

What about after the sum?

- \(W_{+}= 1 + 3 = 4\)

- \(W_{-} + -2 + -4 = -6\)

- Mean: \(\dfrac{n(n+1)}{4}\)

- Variance: \(\dfrac{n(n+1)(2n+1)}{24}\)

What about after the sum?

- Any ties, \(t\): decrease variance by \(t^3-\dfrac{t}{48}\)

- z test:

\[ z =\dfrac{W_{smaller}- \dfrac{n(n+1)}{4}}{\sqrt{\dfrac{n(n+1)(2n+1)}{24}-t^3-\dfrac{t}{48}}}\]

Wilcoxon Signed Rank in R

attach(ree)

wilcox.test(CF, Healthy, paired=T)

detach(ree)

##

## Wilcoxon signed rank test

##

## data: CF and Healthy

## V = 80, p-value = 0.005

## alternative hypothesis: true location shift is not equal to 0

Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test

Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test

- This test is used on indepdent data.

- It is the non-parametric version of the 2-sample \(t\)-test.

- Does not requre normality or equal variance.

How do we do it?

- Order each sample from least to greatest

- Rank them.

- Sum the ranks of each sample

What do we do with summed ranks?

- \(W_s\) smaller of 2 sums.

- Mean: \(\dfrac{n_s(n_s+n_L + 1)}{2}\)

- Variance: \(\dfrac{n_sn_L(n_s+n_L+1)}{12}\)

- z-test

\[ z = \dfrac{W_s-\dfrac{n_s(n_s+n_L + 1)}{2}}{\sqrt{\dfrac{n_sn_L(n_s+n_L+1)}{12}}}\]

Wilcoxon Rank-Sum in R

- Consider built in data

mtcars

library(tidyverse)

cars <- as_data_frame(mtcars)

cars

## # A tibble: 32 x 11

## mpg cyl disp hp drat wt qsec vs am gear carb

## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 21 6 160 110 3.9 2.62 16.5 0 1 4 4

## 2 21 6 160 110 3.9 2.88 17.0 0 1 4 4

## 3 22.8 4 108 93 3.85 2.32 18.6 1 1 4 1

## 4 21.4 6 258 110 3.08 3.22 19.4 1 0 3 1

## 5 18.7 8 360 175 3.15 3.44 17.0 0 0 3 2

## 6 18.1 6 225 105 2.76 3.46 20.2 1 0 3 1

## 7 14.3 8 360 245 3.21 3.57 15.8 0 0 3 4

## 8 24.4 4 147. 62 3.69 3.19 20 1 0 4 2

## 9 22.8 4 141. 95 3.92 3.15 22.9 1 0 4 2

## 10 19.2 6 168. 123 3.92 3.44 18.3 1 0 4 4

## # ... with 22 more rows

Wilcoxon Rank-Sum in R

- We will Consider

mpgandam mpg: Miles Per Gallon on Averageam- 0: automatic transmission

- 1: manual transmission

Wilcoxon Rank-Sum in R

attach(cars)

wilcox.test(mpg, am)

detach(cars)

##

## Wilcoxon rank sum test with continuity correction

##

## data: mpg and am

## W = 1000, p-value = 3e-12

## alternative hypothesis: true location shift is not equal to 0

Kruskal Wallis Test

Kruskal Wallis Test

- If we have multiple groups of independent data that are not normally distributed or have variance issues, you can use the Kruskal Wallis Test.

- It tests significant differences in medians of the groups.

- This is a non-parametric method for One-Way ANOVA.

- Harder to try and calculate by hand, so we will just use R.

Kruskal Wallis Test in R

kruskal.test(formula, data, subset, ...)

- Where

formulaisy~xor can enteroutcome,groupinstead.datais the dataframe of interest.subsetif you wish to test subset of data.

Arthritis Data

- comes from the

BSDApackage. Arthriti

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

time |

Time in Days until patient felt relief |

treatment |

Factor with three levels A, B, and C |

Arthritis Data

library(BSDA)

Arthriti

## # A tibble: 51 x 2

## time treatment

## <int> <fct>

## 1 40 A

## 2 35 A

## 3 47 A

## 4 52 A

## 5 31 A

## 6 61 A

## 7 92 A

## 8 46 A

## 9 50 A

## 10 49 A

## # ... with 41 more rows

Kruskal-Wallis Test in R

kruskal.test(time~treatment, data=Arthriti)

##

## Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test

##

## data: time by treatment

## Kruskal-Wallis chi-squared = 2, df = 2, p-value = 0.4

Spearman Rank Correlation Coefficient

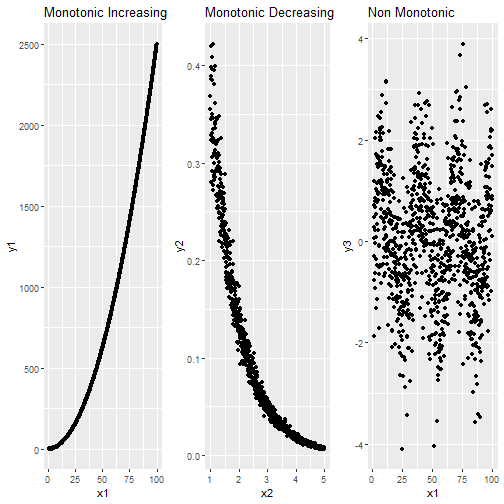

Spearman Rank Correlation Coefficient

- Correlation is a measurement of the strength of a linear relationship between variables.

- This means it does not necessarily get the actual magnitude of relationship.

- Spearman Rank Correlation seeks to fix this.

- It works with Montonic Data.

Monotonic Data

Spearman Rank Correlation in R

- We can do this the the

cor()function.

#Pearson from Monotonic Decreasing

cor(x2,y2, method="pearson")

#Spearman from Monotonic Decreasing

cor(x2,y2, method="spearman")

## [1] -0.887

## [1] -0.996

Smoothing

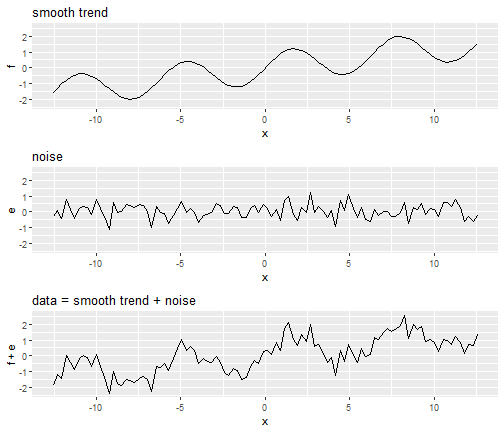

Smoothing

- Smoothing is a very powerful technique used all across data analysis.

- It is designed to detect trends in the presence of noisy data in cases in which the shape of the trend is unknown.

- The smoothing name comes from the fact that to accomplish this feat, we assume that the trend is smooth, as in a smooth surface.

Smoothing

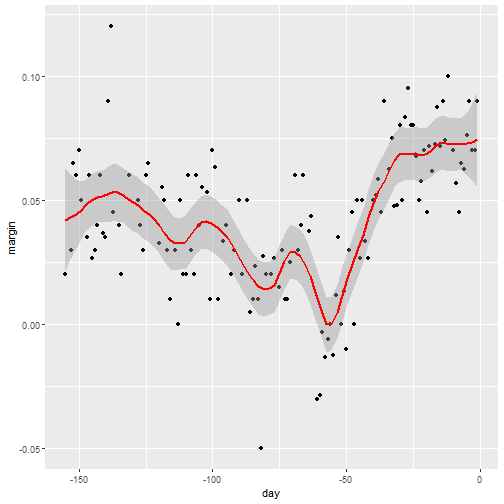

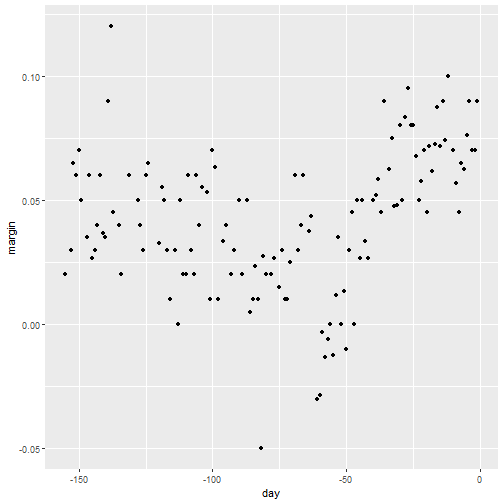

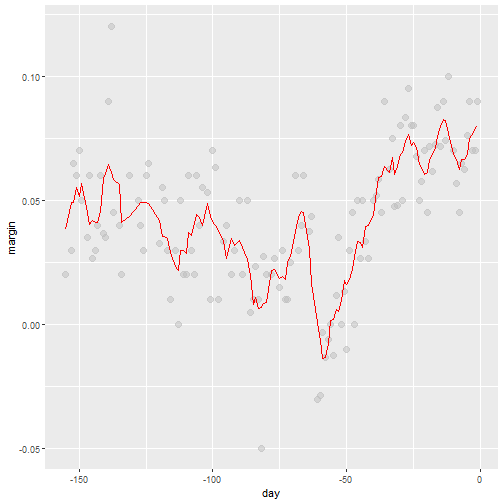

Why Smoothing?

- Lets focus on one covariate

- Let's estimate a time trend on popular vote poll margins

library(tidyverse)

library(dslabs)

data("polls_2008")

qplot(day, margin, data = polls_2008)

Why Smoothing?

Smoothing Example

- We assume that for any given day \(x\), there is a true preference among the electorate \(f(x)\), but due to the uncertainty introduced by the polling, each data point comes with an error \(\varepsilon\).

- A mathematical model for the observed poll margin \(Y_i\) is: \[ Y_i = f(x_i) + \varepsilon_i \]

- If we knew the conditional expectation \(f(x) = \mbox{E}(Y \mid X=x)\), we would use it.

- Since we don't know this conditional expectation, we have to estimate it.

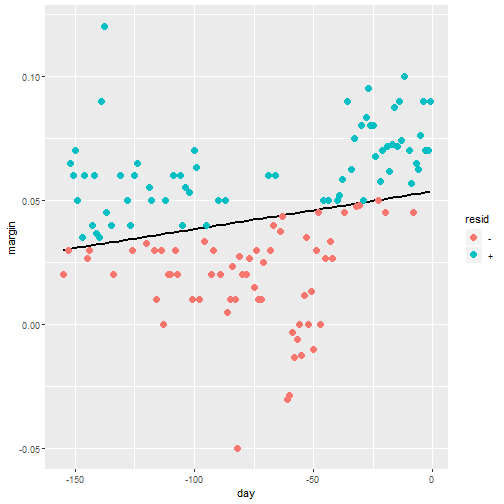

Smoothing Example

- Let's use regression

resid <- ifelse(lm(margin~day, data = polls_2008)$resid > 0, "+", "-")

polls_2008 %>%

mutate(resid = resid) %>%

ggplot(aes(day, margin)) +

geom_smooth(method = "lm", se = FALSE, color = "black") +

geom_point(aes(color = resid), size = 3)

Smoothing Example

Smoothing Example

- The lines do not fit the data well.

- There is not an evenn distribution of positive and negative residuals.

- There is also not a clear pattern like a polynomial terms we could add.

Bin smoothing

- The general idea of smoothing is to group data points into strata in which the value of \(f(x)\) can be assumed to be constant.

- We can make this assumption because we think \(f(x)\) changes slowly and, as a result, \(f(x)\) is almost constant in small windows of time.

- An example of this idea for the

poll_2008data is to assume that public opinion remained approximately the same within a week's time. With this assumption in place, we have several data points with the same expected value.

Bin smoothing

- If we fix a day to be in the center of our week, call it \(x_0\), then for any other day \(x\) such that \(|x - x_0| \leq 3.5\), we assume \(f(x)\) is a constant \(f(x) = \mu\).

- This assumption implies that: \[ E[Y_i | X_i = x_i ] \approx \mu \mbox{ if } |x_i - x_0| \leq 3.5 \]

- In smoothing, we call the size of the interval satisfying \(|x_i - x_0| \leq 3.5\) the window size, bandwidth or span.

- Later we will see that we try to optimize this parameter.

Bin smoothing

- This assumption implies that a good estimate for \(f(x)\) is the average of the \(Y_i\) values in the window.

- If we define \(A_0\) as the set of indexes \(i\) such that \(|x_i - x_0| \leq 3.5\) and \(N_0\) as the number of indexes in \(A_0\), then our estimate is: \[ \hat{f}(x_0) = \frac{1}{N_0} \sum_{i \in A_0} Y_i \]

- The idea behind bin smoothing is to make this calculation with each value of \(x\) as the center.

- In the poll example, for each day, we would compute the average of the values within a week with that day in the center.

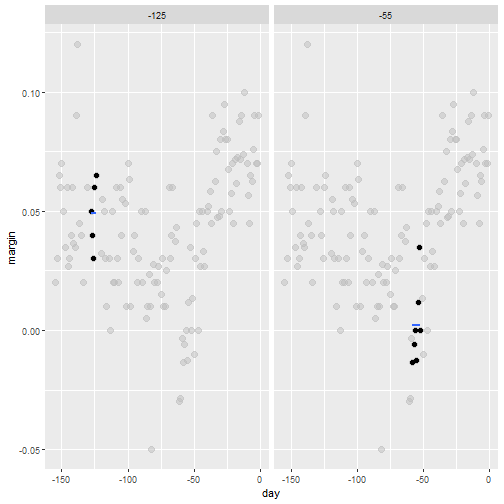

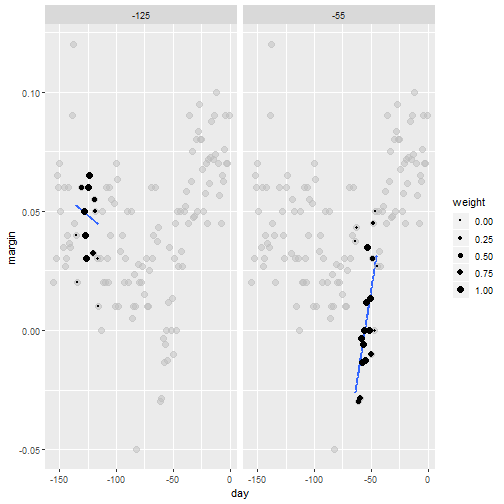

Bin smoothing

- Here are two examples: \(x_0 = -125\) and \(x_0 = -55\).

- The blue segment represents the resulting average.

span <- 3.5

tmp <- polls_2008 %>%

crossing(center = polls_2008$day) %>%

mutate(dist = abs(day - center)) %>%

filter(dist <= span)

tmp %>% filter(center %in% c(-125, -55)) %>%

ggplot(aes(day, margin)) +

geom_point(data = polls_2008, size = 3, alpha = 0.5, color = "grey") +

geom_point(size = 2) +

geom_smooth(aes(group = center),

method = "lm", formula=y~1, se = FALSE) +

facet_wrap(~center)

Bin smoothing

Bin smoothing

- By computing this mean for every point, we form an estimate of the underlying curve \(f(x)\).

- At each value of \(x_0\), we keep the estimate \(\hat{f}(x_0)\) and move on to the next point:

Bin smoothing Animation

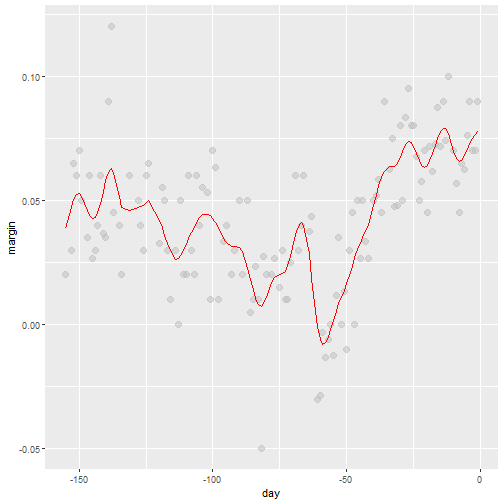

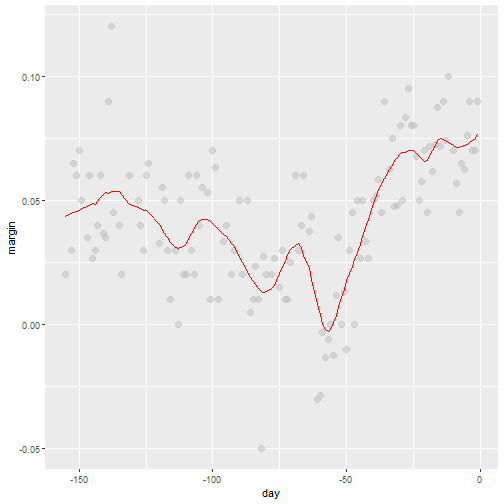

Binsmoothing Results

span <- 7

fit <- with(polls_2008,

ksmooth(day, margin, x.points = day, kernel="box", bandwidth = span))

polls_2008 %>% mutate(smooth = fit$y) %>%

ggplot(aes(day, margin)) +

geom_point(size = 3, alpha = .5, color = "grey") +

geom_line(aes(day, smooth), color="red")

Binsmoothing Results

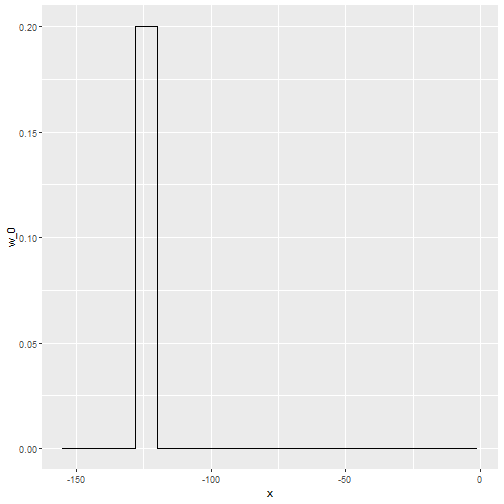

Kernels

- Binsmooth leaves a wiggly results

- This is due to points changing when the window is moved.

- We could weight the center more than outside points to solve this problems.

- Then the outside points no longer have much weight

- This new result would be a weighted average.

Kernels

- Each points receives a weight of either \(0\) or \(1/N_0\), with \(N_0\) the number of points in the week.

\[ \hat{f}(x_0) = \sum_{i=1}^N w_0(x_i) Y_i \]

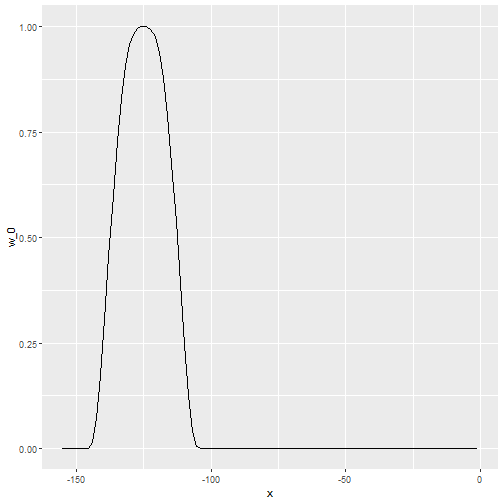

Kernels

- In the code above, we used the argument

kernel=boxin our call to the functionksmooth. - This is because the weight function looks like a box:

Kernels

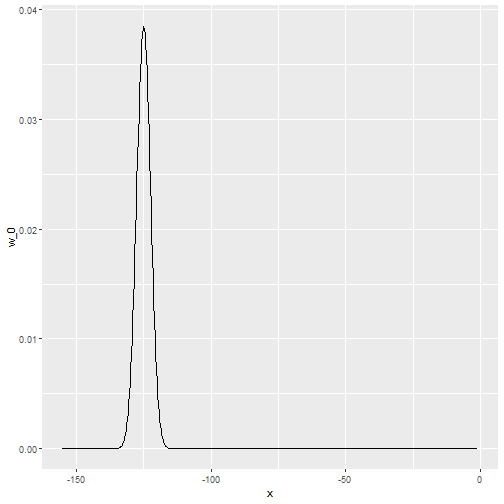

Kernels

- The

ksmoothfunction provides a "smoother" option which uses the normal density to assign weights:

x_0 <- -125

tmp <- with(data.frame(day = seq(min(polls_2008$day), max(polls_2008$day), .25)),

ksmooth(day, 1*I(day == x_0), kernel = "normal", x.points = day, bandwidth = span))

data.frame(x = tmp$x, w_0 = tmp$y) %>%

mutate(w_0 = w_0/sum(w_0)) %>%

ggplot(aes(x, w_0)) +

geom_line()

Kernels

Kernels Animation

Kernels Code

The final code and resulting plot look like this:

span <- 7

fit <- with(polls_2008,

ksmooth(day, margin, x.points = day, kernel="normal", bandwidth = span))

polls_2008 %>% mutate(smooth = fit$y) %>%

ggplot(aes(day, margin)) +

geom_point(size = 3, alpha = .5, color = "grey") +

geom_line(aes(day, smooth), color="red")

Kernels Code

Kernels Comments

- There are several functions in R that implement bin smoothers.

- One example is

ksmooth, shown above. - Usually more complex methods are preferred.

- Even the averaged one is a bit coarse in places.

Local weighted regression (loess)

- A limitation of the bin smoother approach just described is that we need small windows for the approximately constant assumptions to hold.

- As a result, we end up with a small number of data points to average and obtain imprecise estimates \(\hat{f}(x)\).

- loess. To do this, we will use a mathematical result, referred to as Taylor's Theorem, which tells us that if you look closely enough at any smooth function \(f(x)\), it will look like a line.

loess

- Instead of assuming constand in a window, we assumes it is linear in a local area.

- We can then have larger window sizes than just a constant number.

- Let's consider a 3 week window instead of the 1 week. \[ E[Y_i | X_i = x_i ] = \beta_0 + \beta_1 (x_i-x_0) \mbox{ if } |x_i - x_0| \leq 21 \]

- For every point \(x_0\), loess defines a window and fits a line within that window.

loess

loess Animation

library(broom)

fit <- loess(margin ~ day, degree=1, span = span, data=polls_2008)

loess_fit <- augment(fit)

if(!file.exists(file.path("loess-animation.gif"))){

p <- ggplot(tmp, aes(day, margin)) +

scale_size(range = c(0, 3)) +

geom_smooth(aes(group = center, frame = center, weight = weight), method = "lm", se = FALSE) +

geom_point(data = polls_2008, size = 3, alpha = .5, color = "grey") +

geom_point(aes(size = weight, frame = center)) +

geom_line(aes(x=day, y = .fitted, frame = day, cumulative = TRUE),

data = loess_fit, color = "red")

gganimate(p, filename = file.path("loess-animation.gif"), interval= .1)

}

if(knitr::is_html_output()){

knitr::include_graphics(file.path("loess-animation.gif"))

} else{

centers <- quantile(tmp$center, seq(1,6)/6)

tmp_loess_fit <- crossing(center=centers, loess_fit) %>%

group_by(center) %>%

filter(day <= center) %>%

ungroup()

tmp %>% filter(center %in% centers) %>%

ggplot() +

geom_smooth(aes(day, margin), method = "lm", se = FALSE) +

geom_point(aes(day, margin, size = weight), data = polls_2008, size = 3, alpha = .5, color = "grey") +

geom_point(aes(day, margin)) +

geom_line(aes(x=day, y = .fitted), data = tmp_loess_fit, color = "red") +

facet_wrap(~center, nrow = 2)

}

loess Final Smooth

total_days <- diff(range(polls_2008$day))

span <- 21/total_days

fit <- loess(margin ~ day, degree=1, span = span, data=polls_2008)

polls_2008 %>% mutate(smooth = fit$fitted) %>%

ggplot(aes(day, margin)) +

geom_point(size = 3, alpha = .5, color = "grey") +

geom_line(aes(day, smooth), color="red")

loess Final Smooth

loess spans

- Different spans give us different estimates.

- We can see how different window sizes lead to different estimates:

spans <- c(.66, 0.25, 0.15, 0.10)

fits <- data_frame(span = spans) %>%

group_by(span) %>%

do(broom::augment(loess(margin ~ day, degree=1, span = .$span, data=polls_2008)))

tmp <- fits %>%

crossing(span = spans, center = polls_2008$day) %>%

mutate(dist = abs(day - center)) %>%

filter(rank(dist) / n() <= span) %>%

mutate(weight = (1 - (dist / max(dist)) ^ 3) ^ 3)

if(!file.exists(file.path( "loess-multi-span-animation.gif"))){

p <- ggplot(tmp, aes(day, margin)) +

scale_size(range = c(0, 2)) +

geom_smooth(aes(group = center, frame = center, weight = weight), method = "lm", se = FALSE) +

geom_point(data = polls_2008, size = 2, alpha = .5, color = "grey") +

geom_line(aes(x=day, y = .fitted, frame = day, cumulative = TRUE),

data = fits, color = "red") +

geom_point(aes(size = weight, frame = center)) +

facet_wrap(~span)

gganimate(p, filename = file.path( "loess-multi-span-animation.gif"), interval= .1)

}

if(knitr::is_html_output()){

knitr::include_graphics(file.path("loess-multi-span-animation.gif"))

} else{

centers <- quantile(tmp$center, seq(1,4)/4)

tmp_fits <- crossing(center=centers, fits) %>%

group_by(center) %>%

filter(day <= center) %>%

ungroup()

tmp %>% filter(center %in% centers) %>%

ggplot() +

geom_smooth(aes(day, margin), method = "lm", se = FALSE) +

geom_point(aes(day, margin, size = weight), data = polls_2008, size = 3, alpha = .5, color = "grey") +

geom_point(aes(day, margin)) +

geom_line(aes(x=day, y = .fitted), data = tmp_fits, color = "red") +

facet_grid(span ~ center)

}

loess Smooths

## Error in fortify(data): object 'fits' not found

loess vs Normal Bin Smoother

- There are three other differences between

loessand the typical bin smoother.loesskeeps the number of points used in the local fit the same.- When fitting a line locally,

loessuses a weighted approach. Basically, instead of using least squares, we minimize a weighted version. loesshas the option of fitting the local model robustly. An iterative algorithm is implemented in which, after fitting a model in one iteration, outliers are detected and down-weighted for the next iteration. To use this option, we use the argumentfamily="symmetric".

--- .class #id

loess Keeping Same number of Points

- This number is controlled via the

spanargument, which expects a proportion. - For example, if

Nis the number of data points andspan=0.5, then for a given \(x\),loesswill use the0.5 * Nclosest points to \(x\) for the fit.

-- .class #id

loess Weighted Approach

\[ \sum_{i=1}^N w_0(x_i) \left[Y_i - \left\{\beta_0 + \beta_1 (x_i-x_0)\right\}\right]^2 \]

- Instead of the Gaussian kernel, loess uses a function called the Tukey tri-weight: \[ W(u)= \left( 1 - |u|^3\right)^3 \mbox{ if } |u| \leq 1 \mbox{ and } W(u) = 0 \mbox{ if } |u| > 1 \]

- To define the weights, we denote \(2h\) as the window size and define: \[ w_0(x_i) = W\left(\frac{x_i - x_0}{h}\right) \]

-- .class #id

loess Weighted Approach

- This kernel differs from the Gaussian kernel in that more points get values closer to the max:

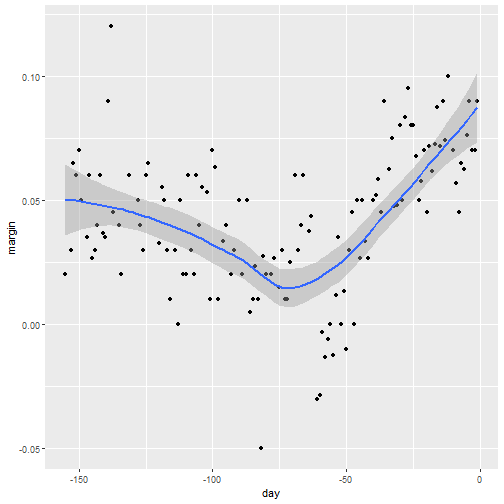

Default Smoothing

ggplotuses loess in itsgeom_smoothfunction:

Default Smoothing

polls_2008 %>% ggplot(aes(day, margin)) +

geom_point() +

geom_smooth()

Default Smoothing

- We can change the default smoothing

polls_2008 %>% ggplot(aes(day, margin)) +

geom_point() +

geom_smooth(color="red", span = 0.15,

method.args = list(degree=1))

Default Smoothing